Where in the World with Julien

Meet Julien! He’s one of our Supervising Archaeologists and joined the Circle crew in August 2024. Julien has already logged more than a decade of archaeology into his career, with fieldwork that stretches from the badlands of Alberta to the volcanic landscapes of Tanzania. He brings curiosity, grit, and plenty of good stories to our team — and yes, a few giraffe traffic jams too.

We caught up with Julien to hear about his journey so far, his favourite places, and the unexpected moments that make fieldwork unforgettable.

What did your journey through school and into the archaeology world look like?

I stepped into my new role as Supervising Archaeologist in May 2025, but my archaeology story goes back much further. I earned a BA and MA in Archaeology at the University of Calgary before heading to McMaster University for a PhD in Anthropology.

My doctoral research took me deep into the McMaster Archaeological XRF Lab under Prof. Tristan Carter, where I studied geological specimens and stone tools from Oldupai Gorge (formerly Olduvai) to figure out where Pleistocene hominins sourced their raw materials. Back in Calgary, I cut my teeth working with Prof. Julio Mercader, diving into everything from stone tools and ancient residues to microbotanical remains and geochemical samples.

The real start of it all, though, was my first archaeology job: a co-op placement with Parks Canada in 2014. That opportunity lit the spark, and more than a decade later, I’m still following it — just with a few more excavations, a few more stamps in my passport, and a lot more stories to tell.

Share a fun fact about yourself or a hobby you enjoy!

When the trowel’s down, I’m probably lacing up my boots for a hike or setting up camp. During the pandemic, that love turned into four unforgettable months living out of a tent in Tanzania, trekking gorges and climbing volcanoes as part of my doctoral fieldwork. These days, I don’t get out quite as often, but I’ve perfected the camp breakfast: eggs, bacon, toast, and cowboy coffee, all timed to a flawless “mise en place.”

I also have a keen interest in all sports, particularly hockey and baseball, as both were huge parts of my youth and early adulthood. However, my only lasting claim to fame from any sport is having played with and against a couple of current NHLers (not a bad line for the résumé).

When I’m not outdoors or talking sports, you’ll usually find me with a book in hand. Historical fiction is my go-to, and I’ve developed a habit of buying faster than I read. Still, every book earns a permanent spot on my shelf, waiting to be explored much like the sites I work on.

In which parts of the world have you worked in archaeology?

My archaeological pursuits have taken me to four countries across three continents. In Canada, I’ve worked in the mountainous interior of British Columbia as well as the boreal forest, badlands, and grasslands of Alberta. During my Parks Canada co-op, I even had the chance to work digitally across a number of national parks, including Nunavut’s Auyuittuq National Park, which is still sitting at the top of my bucket list.

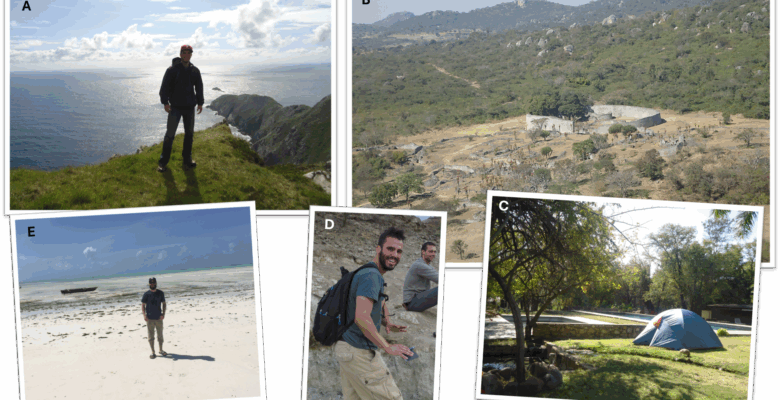

Internationally, I joined fieldschool excavations on Achill, one of the westernmost islands of Ireland (Photo 1A). Our team uncovered evidence that helped tell a story of settlement stretching back to the Middle Bronze Age. During my undergraduate years, I travelled to Zimbabwe with Prof. Julio Mercader. There, we excavated a fascinating Acheulean site with prepared core technology, camped beside a hot-spring-fed pool, and visited the majestic ruins of Great Zimbabwe (Photo 1B–C), not exactly your average field trip.

Later, I was lucky enough to dig at the world-renowned site of Oldupai Gorge in Tanzania (Photo 1D). When I began graduate school, I also carried out botanical sampling on Unguja, Zanzibar, making time for beach walks and snorkeling in between research days (Photo 1E). I eventually returned to Oldupai Gorge several times, sampling dozens of outcrops and working at four excavation sites, fieldwork that ultimately became the backbone of my PhD dissertation.

Which has been your favourite place to work, and why?

Of all the places I’ve worked, Oldupai Gorge in northern Tanzania stands out the most. It’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site with an extraordinary record of human history. This ancient basin, shaped by rifting and volcanic uplift, has preserved an astonishing archaeological record spanning the last two million years of human history.

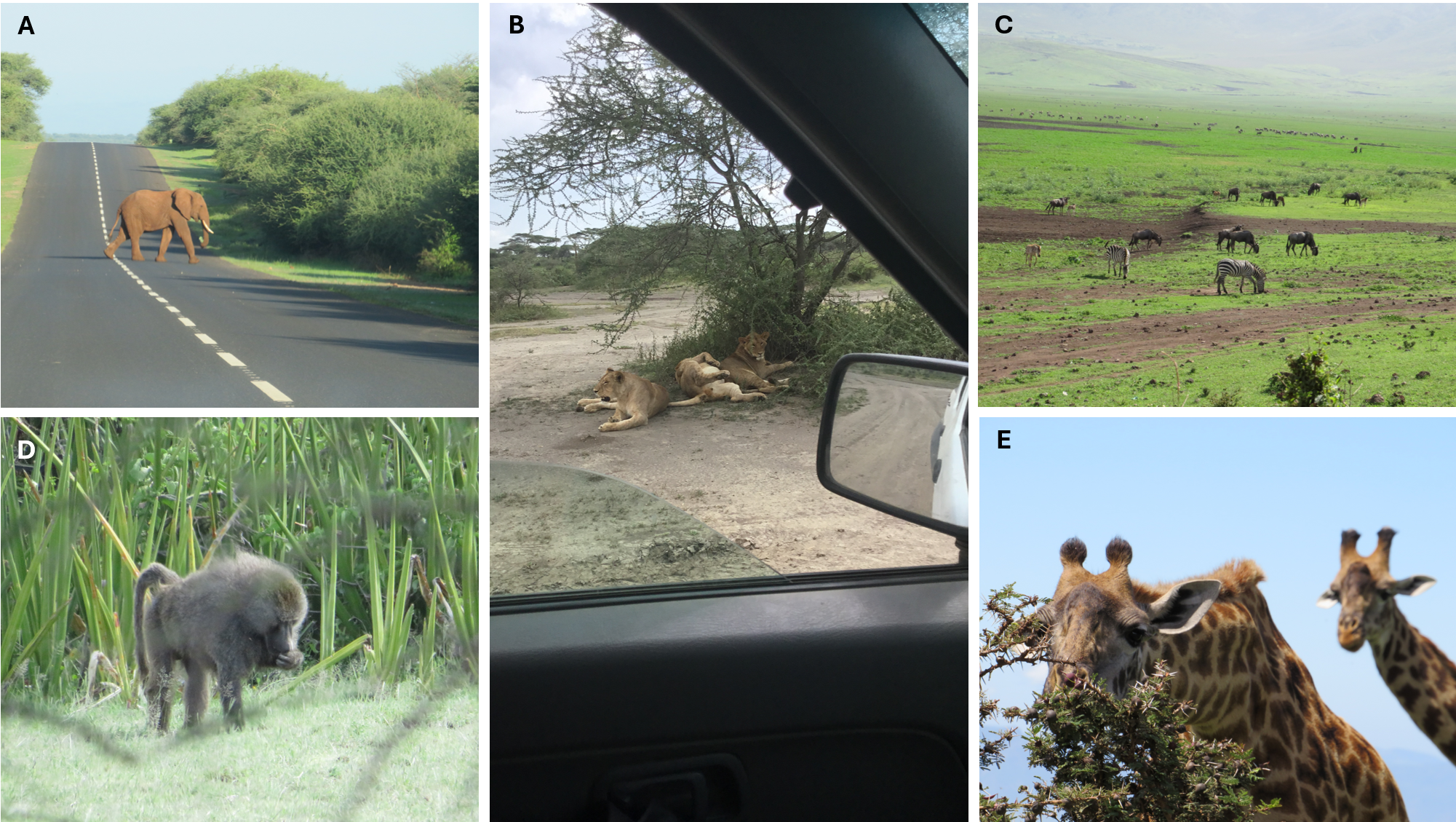

Oldupai is also a landscape of incredible beauty. High-altitude volcanoes, crater lakes, lush mountainsides, seasonal rivers, soda lakes, towering inselbergs, sweeping plains… and the wildlife isn’t shy either. Elephants, buffalo, lions, hyenas, and yes, even pigeons (Photos 2A–D) all call the area home.

The mix of natural wonder and cultural depth makes Oldupai an unforgettable place to dig. And when your daily walk to site includes a few curious giraffes watching you work (Photo 2E), it’s hard not to feel spoiled.

What’s something most would find surprising about a place you’ve worked in?

One surprising part of fieldwork at Oldupai Gorge was the dogs. Living at nearby Maasai homesteads, they kept watch against wildlife and helped with herding, but off duty they often wandered over to our camp. At first it was for treats, but a few quickly became trusted companions, lifting our spirits after long days in the field (Photos 3A–B).

Life without internet in such a remote setting also led to some memorable evenings. I remember friends pulling out a baseball at sunset after a long workday, and before we knew it we had a game going (Photo 3C). Dinner would follow, always a highlight, especially when our camp cook, Reuben Ngwali, turned out fresh bread baked in a repurposed metal crate (Photos 3D–E).

Who knew that camp dogs, a sunset ball game, and bread baked in a metal crate could compete with two million years of history?

What’s your most exciting find?

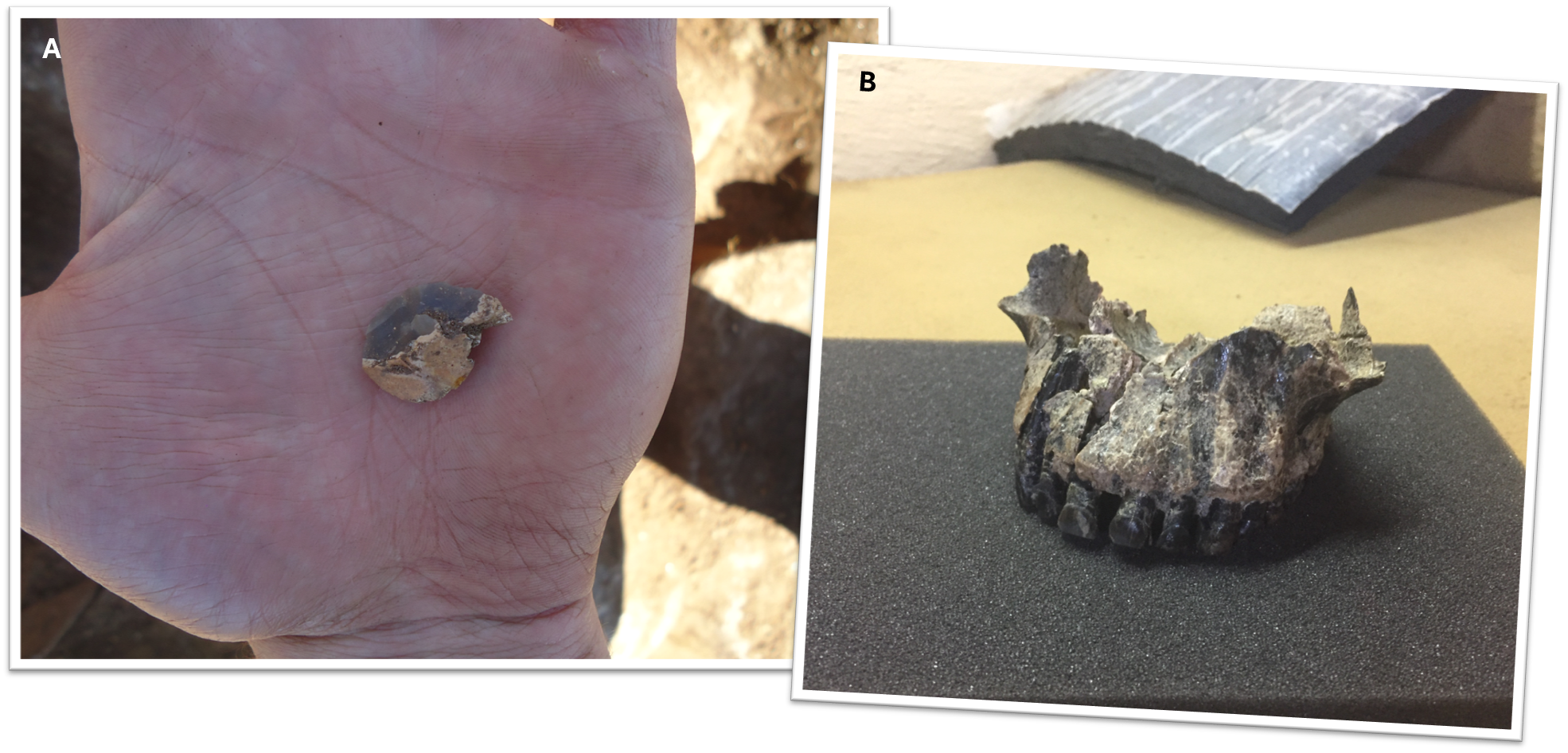

Other than the usual lithics (stone tools), I can’t say I’ve uncovered anything earth-shattering compared to some of my colleagues. But that might change with a little luck. One of my most memorable finds was also my first, a simple chert flake from Achill Island (Photo 4A). It marked the start of a long catalogue of discoveries from a very interesting site.

One of the most remarkable things I’ve witnessed, though, wasn’t my find at all. It was the fossilised upper jaw of an early Homo habilis, teeth perfectly aligned as if frozen mid-smile (Photo 4B). The specimen, OH 65, was uncovered just a few hundred metres from where our team later excavated Ewass Oldupa, now recognised as the oldest Oldowan site at Oldupai Gorge. Its name means “on the way to the Gorge” in the local Maasai language.

Looking back, I’d say being part of those excavations at Ewass Oldupa is the most exciting find, and contribution, of my career so far. Read more about it here.

Do you have any funny stories from the field?

One particularly memorable moment happened on a long, dusty drive from the Ngorongoro volcanic highlands down toward Oldupai Gorge. Our convoy of vehicles came to a halt thanks to what we jokingly called a “Giraffic Jam” — a group of giraffes casually blocking the road while enjoying some roadside snacks, completely indifferent to our situation. Seeing giraffes cause a traffic jam was a surreal experience and definitely not in the driver’s manual (Photo 5).

On another occasion at Oldupai, I woke up convinced we were about to have a run-in with lions. The growling turned out to be violent snoring, as a group of us had to sleep overnight in our truck after some self-inflicted vehicle trouble. That night came with two lessons: first, human snoring can be scarier than a pride of lions, and second, off-road driving with a manual transmission in wet-season mud is not for the faint of heart.

Any advice or insights you’d share with fellow archaeologists?

If there’s one thing archaeology has taught me, it’s the value of seeking out diverse experiences. Whether it is conducting fieldwork close to home or across the world, running experiments in scientific labs, working with community elders, or reading about different time periods and regions, a broad range of experience sharpens your ability to interpret the past and helps you see the forest for the trees.

I would also encourage archaeologists to focus on developing both soft and hard skills. This profession requires many hats and often big teams, so collaboration is just as important as technical expertise. For aspiring archaeologists, professional development should not be limited to courses in your own department. Archaeology is best understood through a transdisciplinary lens. Seek out classes in other fields to broaden your knowledge and build a skillset that will support your professional goals.

Most importantly, enjoy the journey. Wherever you are and however hard it may be, remember that the past is something to be cherished— and the stories along the way aren’t bad either.