Field Notes, Where in the World

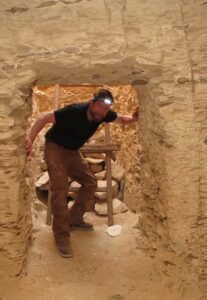

Where in the World With Erik Johannesson

Please enjoy the first post of our newest blog series, Where in the World, where we feature members of our crew who have worked in some pretty unique places as archaeologists. First up, we picked on Erik Johannesson because we knew for a fact he’s worked in some pretty outstanding places and basically inspired this series.

To start off, we asked Erik to share a little bit about himself.

I grew up in Sweden, which has a rich cultural heritage and a landscape studded with prehistoric monuments like tumuli, passage graves, cairns, and dolmens. I remember sitting in my parents’ car, looking out over the horizon and seeing the silhouetted forms of Viking and Iron-Age burial mounds backlit by the moon and starry winter sky. It made an indelible impression on me, and it’s not surprising that now, as an archaeologist, I am interested in stone monuments, ritual landscapes, and mortuary practice. Over the years, I’ve pursued those interests in many different places, from Alberta’s Plains to Russia, Mongolia and Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. It’s been a fun ride so far. When I’m not doing archaeology, I like spending time with my family, playing bass guitar and gardening.

How long have you worked at Circle?

I have worked at Circle for two months but also a few years ago, between 2017 and 2019.

How long have you worked in the field of archaeology?

I’ve been doing archaeology for 23 years and have had the good fortune of working in many places and with some truly brilliant and inspiring people.

What is one piece of field equipment that you can’t live without?

That is difficult to say because you need all of your equipment, don’t you? If I had to boil it down, I’d say measuring tape (or other measuring devices like callipers, scale bars, etc.) because archaeology without spatial context doesn’t really work that well. Also, a camera to document all the interesting things you’re finding. Oh no! See? That’s more than one now.

What was your most exciting find?

Again, it’s almost impossible to pick just one thing. I’ve been lucky enough to find some absolutely wonderful things… and maybe some not-so-wonderful things too. Archaeologists are often more interested in the kind of information an artifact can convey, so I can get as excited about weathering on a small bone fragment or an alignment of rocks as I would a gold brooch. Even when you find nothing at all, it can be very informative and almost just as exciting… well, almost. Archaeologists are often asked, “what’s the neatest thing you’ve found,” and my answer to that question is usually:

– President Jefferson’s ceramic hemorrhoid remover.

– Unborn twins wrapped in textiles from a 2000-year-old tomb (technically, these infants would be classified as perinates or aged to a month before or after birth, but even considering that twins are on average a little smaller than a singular infant, these were too small to have reached full term).

– 2000-year-old Egyptian faience beads in Mongolia. Or evidence of the Silk Road trade before there was a Silk Road.

– A 3500-year-old skeleton where somebody had removed the skull and replaced it with that of a goat.

I pick those because they make for a good story, but then there have been bronze mirrors wrapped in

fur, birch-bark quivers, a ring belonging to a pharaoh, a piece of clay with the tooth imprint of a child; like I said, it’s too difficult to pick just one thing.

Where else have you worked in archaeology?

Internationally, I’ve worked in Mongolia, Russia

(southern Russia and Siberia), Crete, and Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. In North America, I’ve worked in the Southwest (Arizona and New Mexico), the Southeast (North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee) along the Atlantic Seaboard (Delaware, Maryland, and Maine), and in Canada (Alberta, British Columbia, and Nunavut).

What was your favourite place to work and why?

Mongolia. It’s a truly wonderful country with such a rich and colourful culture and extraordinary people. I was blown away by the archaeology when I first travelled there in 2003. It was a landscape of stone monuments reminiscent of that I grew up with in Sweden: carved standing stones (Deer Stones), massive stone mounds with sometimes thousands of satellite features – just mind-blowing stuff. It’s also really remote, with hardly any paved roads outside the capital, Ulanbaatar, and very challenging to work in. In many ways, my approach to archaeology was forged on the steppes of Mongolia, and I am really grateful for all the experiences I had there and the amazing people I’ve met and worked with. I also met my wife on one of the projects there. My life would just not be the same without Mongolia. Working in The Valley of the Kings in Egypt has been pretty cool too, though, and for an archaeologist interested in tombs, something of a capstone. But it’s still not the same as Mongolia.

What’s something most would find surprising about a place you’ve worked in?

There are more non-pharaonic tombs in the Valley of the Kings than those of Egyptian pharaohs. During the New Kingdom, when the Valley of the Kings was in use, it was not called that. It was referred to colloquially as Ta-sekhet-ma’at, or “the Great Field” (formally, its name was, The Great and Majestic Necropolis of the Millions of Years of the Pharaoh, Life, Strength, Health in The West of Thebes, but that’s a bit of mouthful). The point is that it’s more than a burial place of kings. Extended kin, grand viziers, and even Hatshepsut’s wet nurse were also entombed there. There’s even a tomb for baboons and a dog belonging to the pharaoh Amenhotep II.

Anything else you want to share about your experiences?

The Trans-Siberian Railway is a great experience, but from Moscow to Novosibirsk, it passes mostly through forests, so get ready for views of trees. The awe-inspiring vistas are along the railway’s east, from Novosibirsk to Ulan-Ude (not the final stop), so that’s actually the route you’re better off booking if you’re looking for a picturesque travel adventure.

Do you have any advice or  information for other archaeologists?

information for other archaeologists?

Read! Read things outside of your own research area, out of your comfort zone, about anything and everything. Reading will give you a broad framework of reference from which to engage whatever it is you’re working on. Innovation and breakthroughs rarely come from doubling down on what we already know on a given topic. It’s usually the knowledge of something else, applied in new ways, that leads to innovation. Reading will provide you with that.

Do you have a fun anecdote from the field?

There are so many. They’re best shared over a coffee or a beer, so ask me about it when you see me. Of course, I’m always game to hear stories of field adventures too. Fieldwork is great fun. It’s what makes our profession so unique and special.