Females in the Field, Field Notes

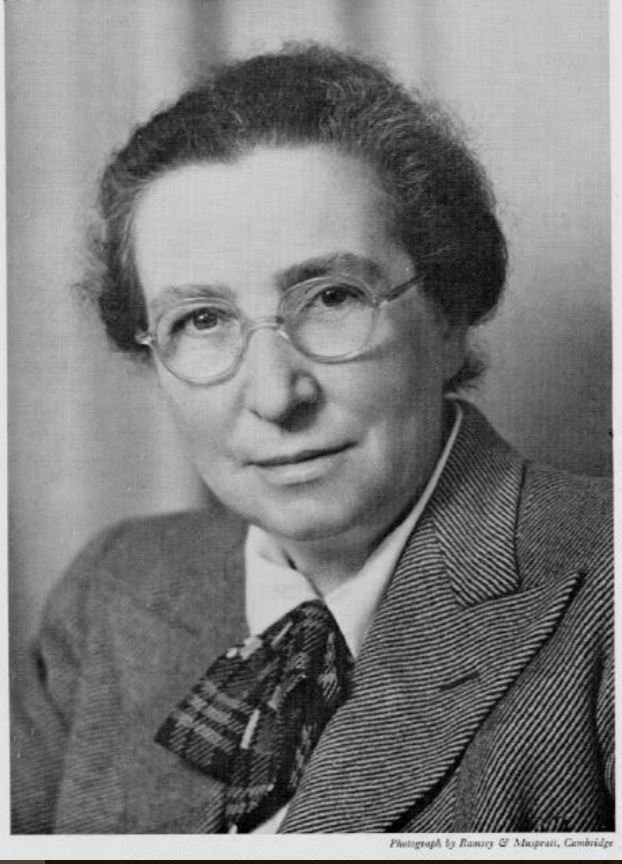

Women in Archaeology: Dorothy A.E. Garrod

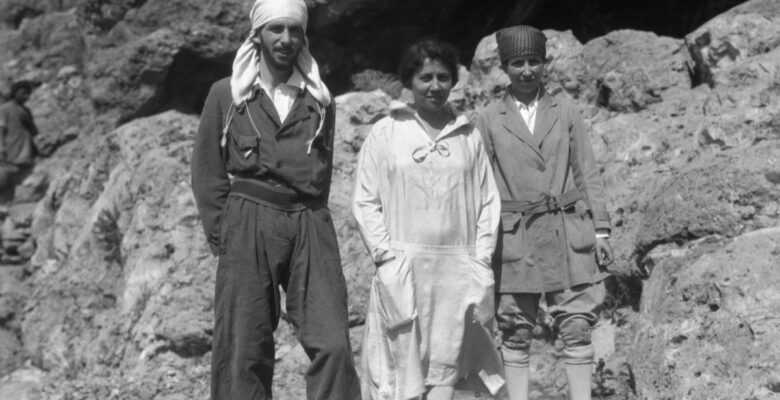

Photo by: Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Written by: Erik Johannesson

In honour of Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day, we are debuting our Women in Archaeology series where we highlight both the remarkable careers of women in our field and the lives of extraordinary women in the past. For our first feature, we have Dorothy Garrod, a true trailblazer and perhaps, one of the most influential prehistoric archaeologists of the early 20th century. Her contributions to the field of Archaeology, and particularly the study of the Upper Paleolithic, are still keenly felt today. Among her many accolades, she was the first woman to ever hold a chair at either Oxford or Cambridge. Get a glimpse into her truly exceptional life and career, below!

Garrod was born in 1892, at a time when women were still denied many basic rights and opportunities. The right to vote was still some time off, and women’s education was only in its infancy; Women were denied full membership in universities. While Dorothy was raised in a home that valued intellectual achievement, expectations in Victorian England tasked her brothers with carrying on the family tradition. Thus, until she was nine years old, Dorothy was taught at the family home by a series of governesses, including the famous social activist Isobel Fry, who took her to visit Roman Verulamium and instilled in her a life-long interest in the past. She entered Newnham College to study History and Classics in 1913, but change and turmoil lay ahead.

The Great War, like it did for so many, brought tragedy to the Garrod household. Dorothy lost two brothers and her fiancé in the war, and her third brother died of the influenza that swept the world in its wake. Dorothy would later remark that as the family’s sole survivor of her generation, she felt compelled to uphold her family’s intellectual tradition by making up for the unfulfilled achievements of her lost siblings through her own accomplishments. Determined and inspired by prehistoric sites on a trip to Malta, Dorothy registered for a university diploma course in Anthropology at Oxford under the famous Robert R. Marett, graduating with distinction in 1921. Her mentors and peers during this formative period are a literal who’s-who of early 20th century scholars – R.R. Marett, Abbé Breuil, and Tailhard de Chardin. One of her first tasks was to study the Somme Gravels, the very material from which the European Paleolithic was first identified in the 1840s. To add to this, Garrod was about to make her own indelible mark on the discipline.

In 1925, she discovered the remains of a Neanderthal (now known as the Gibraltar 2 specimen) at Devil’s Tower Cave in Gibraltar. She followed up this extraordinary discovery with the book The Upper Paleolithic of Britain in 1926, the first exhaustive volume of its kind on the Paleolithic of the British Isles and continental Europe. Remarkably, and a testament to her insightfulness, most of Garrod’s conclusions were still valid several decades later when another effort to summarize the British Paleolithic was attempted by John Campbell in 1972.

In 1928, she was asked to direct excavations at Zardi Cave and Hazard Merd Cave in what today is northern Iraq, where she discovered Upper Paleolithic materials and established the area as a source of early human and Neanderthal prehistory. This paved the way for future archaeologists to explore the area, eventually leading to Ralph Solecki’s famous discovery of the Neanderthals at Shanidar in the 1950s. Without Garrod’s pioneering work, it is doubtful that these later investigations would ever have taken place.

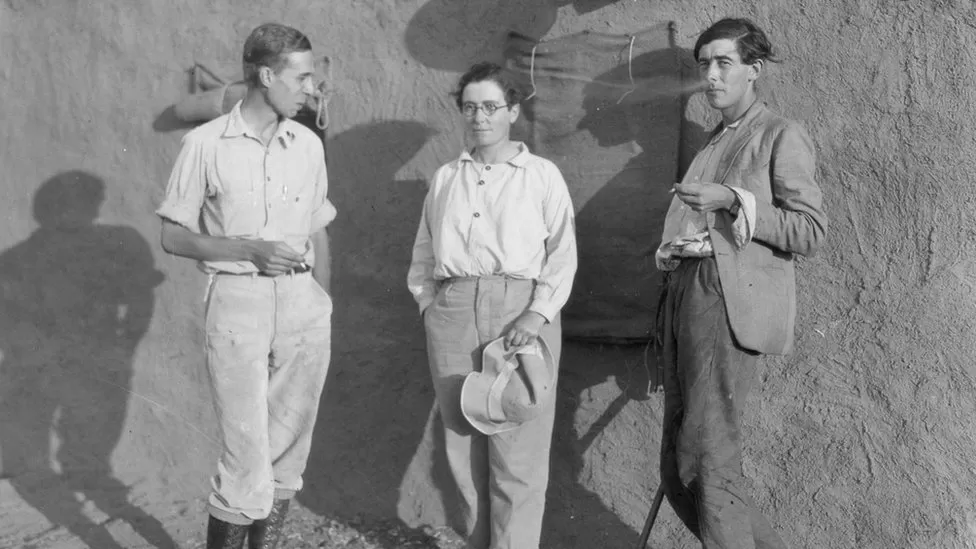

Garrod’s work at Tabun, Skhul, and Kebara caves in Israel are still critical to our understanding of the origins of modern humans and the demise of the Neanderthals, but it was her work at the El-Wad and Shukbah caves that remains one of her primary contributions to the field. Here, she uncovered evidence of early farmers, a society she named Natufian culture, that predates the important transition to agriculture in the Near East. Among the remains were stone sickles, microliths (small stone tools), carved figurines, and bone beads. Garrod firmly established the presence of Natufian culture in the regional chronology of the Near East, and these assemblages are still viewed as among the earliest known examples of agriculture in the world.

In 1939, Garrod was elected Disney Professor of Archaeology at Cambridge, becoming the first woman in history to ever hold a chair at either of England’s distinguished universities. This was an extraordinary achievement, made all the more noteworthy when one considers that she beat out both Christopher Hawkes (he of the ladder of inference fame) and Miles Burkitt for the job. Later, she was elected Fellow of the British Academy in 1952, received the Huxley Memorial Medal of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1962, and was awarded the Gold Medal of the Society of Antiquaries in 1968.

Dorothy Garrod was keenly aware of the obstacles facing women, both in the field of archaeology, and in the academy in general. She often made a point of including and promoting women through her projects. Her field crews were usually composed of a majority of women, and she typically included women as supervisors, which was unusual for the time. Abroad, she often assembled crews staffed mainly by women from local villages, thus setting a precedent for practices seen more recently in the community archaeology today. As such, Garrod was a force of change, and many of her students went on to have distinguished careers themselves; Lorraine Copeland, Olga Tufnell, and Ruth Amiran, among them.

Dorothy Garrod’s career shattered glass ceilings, and many of her accolades represent the first time that a woman had obtained them in England. She set new standards in archaeology, both in terms of methods and practice, and strove determinedly for a greater sense of ethics and equality in the field.

When once asked how much of her life had been up to luck, Garrod famously replied, “It’s not luck. It’s courage and perseverance.”